Wabi-sabi by Schattdecor

The ancient aesthetic principle wabi-sabi is deeply rooted in Zen Buddhism. Via Instagram, it has now arrived in the West. Its object design is melancholic: it depicts the transience of things. Provided we engage with its message, we are being trained to "accept the suffering in ourselves". This fits perfectly into our time. Welcome to the third part of our Cocooning trilogy!

Wabi-sabi is on everyone's lips! With this introduction we will spare ourselves the obligatory tongue-in-cheek reference to the similar-sounding, hot-as-hell horseradish plant. Instead, we direct our attention to the radiance of a traditional beauty ideal that has been known in parts of Asia since the 16th century and is still present in everyday life today.

Wabi-sabi Has Arrived In the West

Via globalization, digitization and social media, wabi-sabi has recently expanded beyond Asia and its melancholic message is beginning to resonate with baffled Westerners. Wabi-sabi objects are suddenly everywhere, asking us to see them, understand them, and give them space within our existing design and thought processes.

"Admire the cherry blossoms

only in their full glory,

the moon only in a cloudless sky?

Longing for the moon in the rain,

sitting behind the bamboo curtain,

without knowing how much spring has already come –

that too is beautiful and touches us deeply."

–Yoshida Kenkō, Zen monk,

around 1283 to around 1350

For many people, however, the Eastern ideal of beauty is not quite so easy to grasp - Western societies are too far removed from the philosophical idea that everyday objects can tell us stories. And then we lack the terminology alone to be able to translate Wabi-sabi one to one into our languages or cultures. As with “Hygge” in Part 1 of this trilogy of articles, we have to approach the description of a foreign design semantics in a wordy fashion. We learn that wabi means "to feel alone, miserable, lonely, abandoned, and lost." Sabi, on the other hand, also means alone, but then also aged, matured, covered with patina.

Does that help us? No. A quick look on Instagram, #WabiSabi. Aha. Google image search "Wabisabi". Aha, aha!

With the help of content, images and looks, we approach the wabi-sabi feeling. Many questions still remain unanswered: From what and from which world views does this ideal of beauty actually draw? Why do we find it so difficult to decipher it intuitively?

Our Schattdecor designers have come up with a few carefully decelerated thoughts to clarify this. And they are worth reading up on. After all, designer narratives of quiet contentment over simple things fit our times quite wonderfully.

What Aesthetic Ideals Have Shaped Us In Europe?

Understanding wabi-sabi purely through its word meaning or through its objects is, as already mentioned, not effortless for Western educated people. The principle seems somehow strange and somehow complicated to us at first glance. So let's take a detour and first clarify our own ideals of beauty, in order to then approach the foreign perspective.

And off we go: This article, for example, was written in Vienna surrounded by the imperial-royal pomp of the Habsburgs. The beauty ideals of Greek antiquity can be found everywhere in the streetscape here. From the baroque Hofburg to the parliament building—which pretends to be a Greek temple—to the Schönbrunn Palace, countless examples of Viennese architecture are full of the messages of the emperors of the Holy Roman Empire. Designed for the eternity of a five-century ruling dynasty, these objects communicate the aesthetics of the West: durability, size, symmetry and perfection.

Nature In Western Ideals of Beauty

The cities of Europe are full of such narratives of imperial omnipotence. Even nature has been portrayed in a regulated manner within Western aesthetics for thousands of years, and seemingly perfect phenotypes have been overemphasized: Based on this logic, the palace gardens of Europe do not portray the 98 percent of imperfect nature, but rather the 2 percent of nature that appears perfect. This stylizes man as the crown of creation, who tames nature as God's representative.

A long-term consequence of our centuries of programming for perfection and power is that most objects in the West today only count for something if they are symmetrical, pristine, and in mint condition. With the first signs of use, they are worth less or even nothing; eBay sellers could write novels about this. A car loses up to two-thirds of its value when new just through the act of purchasing it – it doesn’t need to have been driven a meter for that to take place. Of course, this tells us something about the high value that brand-new things have in our societies. The fact that the Vienna Parliament and Schönbrunn Palace have to be constantly renovated at great expense so that they can live up to the aesthetic standards ascribed to them ... that’s another story.

Back to Wabi-sabi

One would like to say: the complete opposite of wabi-sabi. The melancholy design of wabi-sabi items is humble. It tells no stories about the status symbols of individual gods, people, dynasties or cultures. Rather, its narratives aim for a spiritual dimension, as wabi-sabi objects celebrate the contemplative moment and the beauty of the imperfect. Quite unlike in Europe, impermanence, modesty, asymmetry and imperfection emerge as social values in wabi-sabi objects. With Wabi-sabi design, each piece becomes a homage to the temporality of things, a declaration of love to the poetry of the imperfect. For example, a house roof that is not as sterile, perfect and clean as it could be, but deliberately overgrown with moss. Here a tea kettle is marked by patina and an unsightly crack emblazoned on the ceramic bowl.

In the wabi-sabi approach, creative virtuosity is not judged by how many carats of gold have been used, but by how faithfully the objects created reflect reality.

With the formation of the signs of their aging, objects gain individuality and character. Their flaws and blemishes trigger empathy in us and elicit appreciation from us. Why? Because, like us, they obviously have a personal story to tell. In recognizing this similarity, we take the first step towards identification with and attachment to the object. By allowing Wabi-sabi design to have an affect on us, by personifying it, a window opens through which we recognize our own impermanence.

"I have good news and bad news too.

First the bad: We will crumble to dust.

We turn to ashes, return to the nothingness

We all once came from.

And now the good news: Not today!

There is still time for you and me.”

–Danger Dan, "Good News [Eine gute Nachricht]" (2021)

Our Path To Wabi-sabi

Wabi-sabi opens up a new approach to object design for us westerners. The humble idea that both we and our human creations can, and should be, imperfect and impermanent, and to show that we are all subordinate to something greater than humans, softens us. It defragments our inner clutter and brings us closer to contemplation, calm, depth, relaxation, contentment and inner richness. With this realization, at the latest, we end up back at what the Japanese tea master and Zen monk Sen no Rkyū had already put in a nutshell five hundred years ago:

"In the cramped tea room, it depends on the fact that the utensils are all somewhat inadequate. There are people who reject a thing at the slightest flaw—with such an attitude you only show that you have understand nothing."Sen no Rikyū, Japanese tea master and Zen monk, 16th century

Wabi-sabi Objects Ask Us To Think About Them and About Ourselves

Whenever we really engage with an object, we begin to dream – and it doesn’t matter whether it's about a castle in Vienna or a wabi-sabi object with an artfully designed blemish. But what we dream about derives from fundamentally different ontologies: The message of a wabi-sabi object is approachable. Unlike Schönbrunn Palace, it makes no secret of the fact that it will be subject to wear and tear. Because transience is inscribed in the design right from the start, we build a relationship with the object, with its creator and with ourselves, while the Viennese architecture leaves us in amazement. Wabi-sabi design transports us straight into the poetic, as the object itself engages in storytelling: we all appear as meaningless sidekicks in a never-begun, never-ending play called Time.

Man and Time

When we get involved in the romantic-spiritual narrative of such an object's design, we can suddenly feel how gigantically large eternity is and how tiny and ephemeral we humans are. We must feel a kind of melancholy about this. A vague hope descends on us. We begin to yearn for something on which our existence can be rooted, something that makes our own existence tangible and explainable. On the other hand, we feel grateful that we humans—like this object—are allowed to play a role in the here and now, even if only for a short time.

When we confront the object, we understand that we should not value the object itself, but instead, the tiny moment that is given to us on earth. And surprise: Japanese also has its own word for these sensations that wabi-sabi objects trigger in us – Mono no aware. It describes exactly that feeling of sadness that traces the transience of things, but ultimately comes to terms with it.

Self-efficacy In Rough Times

Why the Wabi-sabi design is so popular right now is obvious from our point of view. We live in tough times when our need for meaning, for honesty and truthfulness demands answers. We slow down our lives, tidy up, get rid of things, create order and try to regain control, if not over an increasingly crazy world, then at least of our own lives.

The Making of Wabi-sabi

Meanwhile, in our living space, we are developing an unprecedented preference for lively, organic material structures, design language and spatial aesthetics: the imperfect, the aging of objects from weather or use are viewed as perfect and aesthetically complete in Japan. This also helps us in these times, because the imperfections and irregularities nourishes our soul much more than the perfect ever could.

In design, wabi-sabi thrives on contrasts between light and dark as well as a natural feel that radiates honesty and credibility. This is how traditional Japanese crafts constructs “perfect imperfection”.

How Much Wabi-sabi Is In Schattdecor?

It’s fair to ask whether this ideal of beauty can also be applied to modern, industrially produced objects. And the answer is: of course! The quality criteria are asymmetry, simplicity, the degree of weathering as well as proximity to nature, functional inadequacy, detachment from the worldly - and a quiet atmosphere.

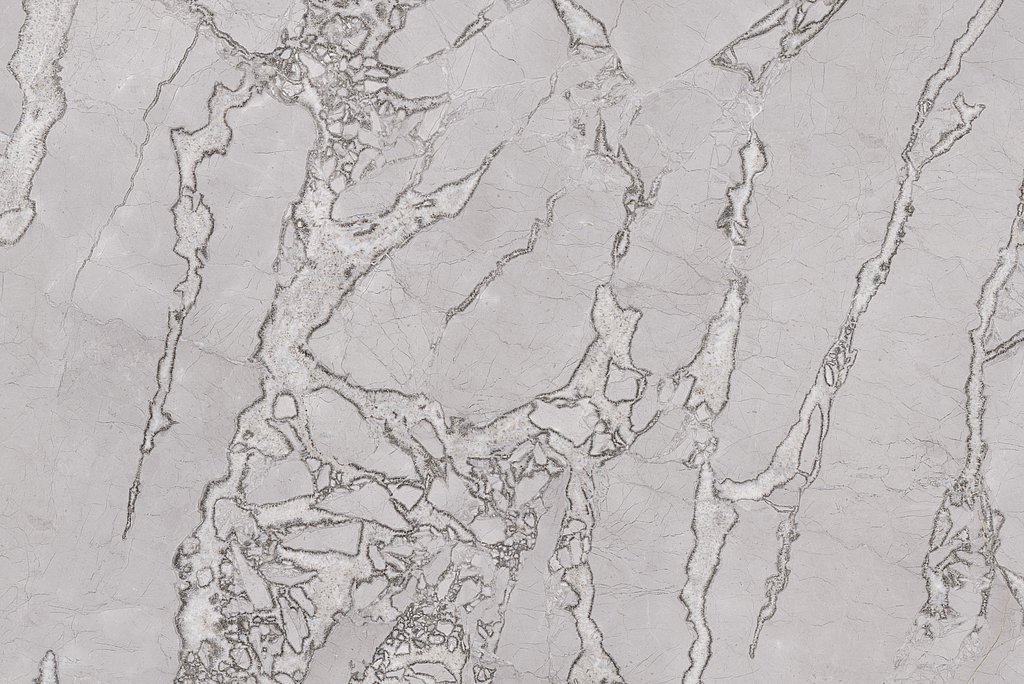

Liam Gold, 4000501-01-000

Eastern and Western Ideals of Beauty

A standard of beauty is neither good nor bad, one is not better than the other. But is it exciting to decode historical, philosophical, religious, cultural and social codes in order to learn more about one’s own worldview.

Podcasters Melissa Lee and Marco Walz from the German-language channel NIPPOD, for example, call Japan — in contrast to the West — an "aesthetically structured country". While the Japanese have lived the aesthetics of wabi-sabi in everyday life for centuries, even today, we can hardly understand Greek mythology in the design of our own cultures.

Wabi-sabi works through our curiosity, our imagination and our capacity for knowledge. It works through accepting a truth that is infinitely greater than ourselves. Mindfulness of the object is the key to unlocking that truth. And who knows? Thanks to our newly won ability to contemplate, we may even find the lost key to the ancient aesthetics of Europe.